This post goes with a short presentation I’m doing at the NSCAA — I mean, United Soccer Coaches (snappy short title to come, but I’m going to say UniSoc here) — convention for the Society for American Soccer History, an organization that has caught fire in the past three years or so.

1941: National Soccer Coaches Association of America (NSCAA) is formed. Coaching education would be a major focus, and the organization would go on to offer its own coaching courses and diplomas, especially ramping up in the mid-1980s. Its conventions aren’t just an attempt to set a world record for the number of tracksuits in one convention center — coaches would flock to them for lectures and demonstrations from pro coaches from the USA and elsewhere. The organization is now known as United Soccer Coaches.

1964: The American Youth Soccer Organization (as with the NSCAA or NASCAR, no one ever uses the full name — it’s “AYSO” to everyone) is formed, offering a different approach than existing youth leagues — it’s open to all, every player plays, and teams are shuffled in the name of parity. Though it remains mostly recreational, with no pretense of being “elite,” it develops some outstanding players (Alex Morgan, Landon Donovan, Carlos Bocanegra, Eric Wynalda among them). It would also develop its own coaching education resources down the road, many of them proprietary. So if you live in an area with no AYSO operations (say, most of my home state of Virginia), you can’t see them.

1970-74: U.S. Soccer Federation coaching begins in earnest with the first course in 1970, which trains several future national team coaches (one of them also a future New York Cosmos coach). The man credited with setting up the curriculum is Dettmar Cramer, who arrived from Germany via Japan and served a brief stint as USMNT coach in 1974.

Sources: Cramer obituary in Soccer America, interview with Ian Barker (United Soccer Coaches director of coaching education)

1980s: Bob Gansler, later the USMNT coach and then director of coaching at U.S. Soccer, helps develop NSCAA coaching education (Source: interview with Ian Barker, United Soccer Coaches director of coaching education).

Source: interview with Ian Barker

1995: U.S. Youth Soccer introduces the National Youth License, a weeklong course that focuses on U12 (and under) and emphasizes psychology and teaching. In 2015, it is renamed the National Youth Coaching Course.

2011: Claudio Reyna unveils the new U.S. Soccer curriculum at the NSCAA convention. Some coaches and journalists are puzzled by the admonition against “overdribbling,” and they’re skeptical that the USA can ever settle on one approach. The curriculum is indeed quite specific — teams are supposed to play a 4-3-3 (slightly revised to 4-2-3-1 or 4-1-2-3 as needed, and possibly 4-4-2 at some older age groups), and coaches are told which skills to emphasize at which ages. Within a few years, it quietly fades into disuse.

Sources: U.S. Soccer curriculum, My report for ESPN

“U.S. Soccer, it’s always been kind of ‘What’s the new flavor of the day?’ So if the Dutch were successful, the U.S. would kind of mimic how the Dutch do their systems of play. And then the Germans start winning, you know, I think the U.S. was always looking over in Europe, even South America, for ideas and different ways. And they would bring over a lot of foreign coaches as well to kind of help with some lectures and things like that to give us some ideas about how they do it overseas coaching-wise.”

Mark Pulisic (yes, Christian’s father — also an experienced coach). Source: 2018 interview with PennLive

2011: Dave Chesler hired as U.S. Soccer Director of Coaching Development.

2013: The NSCAA and Ohio University launch a master’s degree program in soccer coaching.

Source: Ohio University program information

2013: USSF D license (geared toward coaches at U13 and U14) now includes concepts such as periodization, useful for high-level coaches but not really applicable to grassroots coaches. It also requires coaches to take the two weekends of work — “Instructional Phase” and “Performance Review” — with a minimum of 10 weeks in between.

Sources: 2013 USSF release via SoccerWire, 2014 U.S. Soccer Q&A with then-Director of Coaching Development Dave Chesler

2014, February: Ryan Mooney hired as U.S. Soccer Director of Sport Development.

2015, February: U.S. Soccer slams the door on the alternate coaching pathway that allowed coaches to skip lower-level USSF courses if they had the rough equivalents from NSCAA. (Someone with an NSCAA National Diploma for a year could move into USSF C license course; someone with Advanced or Premier Diploma for a year could move into B license course.) Most controversially, the policy takes effect immediately.

Sources: Multiple, including 2018 Soccer America Q&A with Ian Barker. Can compare USSF policies from 2012-13 and 2017-18, copied and stored at Box.com

It’s philosophical, because their curriculum approach isn’t aligned with ours. That’s like you’re being taught French, and you’re saying, hey, it’s a Romance language, so it should be equivalent to my Italian course.

Then-USSF Director Chief Soccer Officer Ryan Mooney, speaking with Soccer America in 2018

There is a progression of complexity for tactics that is important. Having coaches come into the pathway at different points is not very functional, so our vision is for a coach to enter our pathway and be in it throughout their entire coaching career.

Then-USSF Director of Coaching Development Dave Chesler, speaking with ussoccer.com in 2015

2015, February: Several soccer organizations not normally on the same page — U.S. Youth Soccer, US Club Soccer, AYSO, Say Soccer, U.S. Futsal, U.S. Specialty Sports Association and MLS (?!) — form a Youth Council Technical Working Group that demands more openness from U.S. Soccer in discussing issues such as the birth-year age-group mandate and coaching licenses.

2015, February: USSF releases new F license (for coaches of U8 and lower) online, effectively taking away the excuse of parent coaches to not take the F license. It features examples of coaching from people such as Shannon MacMillan.

Sources: My SoccerWire story, group statement

2015, June: Nico Romeijn hired as U.S. Soccer Director of Coaching Education. Chesler remains as U.S. Soccer Director of Coaching Development. Mooney remains as U.S. Soccer Director of Sport Development.

2015, December: First graduates of new USSF Pro License course get their licenses.

2016, January: Chesler leaves Director of Coaching Development post.

2016, September: The NSCAA, anticipating a similar move by U.S. Soccer, overhauls its grassroots coaching curriculum, replacing its Level 1 through Level 6 diplomas with a brief online intro and then several age-appropriate pods.

Sources: United Soccer Coaches (formerly NSCAA) coaching courses (click “Development” to see the grassroots modules)

Sources: U.S. Soccer release, Soccer America

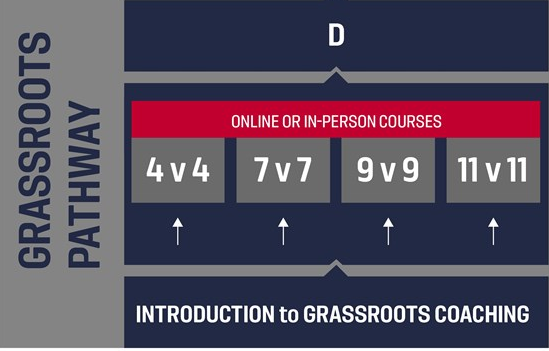

2018, January: U.S. Soccer unveils its own new grassroots modules, allowing coaches to start with a basic intro and then take age-appropriate modules either online or in-person. The modules are rolled out over eight months. The old F license and E license are gone, but you can still progress to the D license three ways …

First: If you have the E license, you only need to watch the Intro to Grassroots Module online.

Second: If you have the F license, watch the Intro module and take two in-person modules, including the 11v11 module.

Third: If you have neither of those (in other words, you’re starting fresh), watch the Intro and take three modules — one online of your choice, one in-person of your choice, and the in-person 11v11.

Also, the new training format is “Play/Practice/Play” — coaches are asked to have players immediately jump into small-sided games as soon as they arrive, with coaches speaking over the flow to subtly introduce the topic of the day, then have the “practice” phase, then scrimmage. And at least in the classes I took, we were encouraged to grab practice plans from U.S. Soccer or elsewhere rather than devising them ourselves. The new practice plans are indeed simpler to use.

Sources: Maryland Youth Soccer Association (thanks for posting, guys), Soccer America

This is an improvement over the “Warmup with a drill that takes a little bit of time to explain / Small-Sided Game that takes a little bit more time to explain / Expanded Small-Sided Game that’s ridiculously complicated and will never be explained over the course of this practice / Scrimmage” approach, in which we were all supposed to develop practice plans like we’re Fabiano Caruana prepping to face Magnus Carlsen for the world chess championship in November.

Source: My review at Ranting Soccer Dad. By the way, Caruana nearly won.

2018, April: New U.S. Soccer org chart shows Nico Romeijn as Chief Sport Development Officer and Ryan Mooney as Chief Soccer Officer. Coaching education is listed as a responsibility of each person. Concurrently, USSF announces a Technical Development Committee overseen by Carlos Bocanegra and Angela Hucles, the Athletes’ Council representatives to the USSF Board.

2018, August: Romeijn and Mooney discuss availability of upper-level licenses and insistence that Development Academy coaches must have a least a B license in interview with Soccer America’s Mike Woitalla. The USSF officers’ comments draw heavy criticism from ESPN’s Herculez Gomez, focusing on the accessibility of these program to Hispanic coaches.

Source: Soccer America Q&A, Ranting Soccer Dad account of Gomez criticism and other issues

2018, October: A U.S. Soccer-led task force on youth soccer, promised by Carlos Cordeiro in his successful campaign to become federation president, convenes for the first time.

2018, December: Asher Mendelsohn hired as new U.S. Soccer Chief Soccer Officer, replacing Ryan Mooney, who has gone into a private venture. No word as yet as to whether Mendelsohn and Romeijn’s responsibilities for coaching education have been adjusted or clarified.

Source: Soccer America report

TODAY …

United Soccer Coaches continues to offer its own grassroots modules in addition to a more advanced sequence — National, Advanced National, Premier — as well as separate courses on goalkeeping, futsal, high school coaching, club administration (in conjunction with US Club Soccer), LGBT inclusion, safety and tactics. It also collaborates with the University of Delaware for a Master Coach Diploma / Certificate and with Ohio University on the master’s degree mentioned above.

US Club Soccer and AYSO are doing their own thing.

MY COACHING COURSES

- 2010: F license through Virginia Youth Soccer Association

- 2013: Second Positive Coaching Alliance workshop

- 2013: E license, USSF

- 2014: NSCAA Special Topics Diploma: Coaching U6, U8, U10 Players

- 2014: Incomplete D license, USSF (instructional weekend only)

- 2015: F license, USSF online version

- 2017: United Soccer Coaches Diploma: Get aHEAD Safely in Soccer

- 2018: USSF Introduction to Grassroots Coaching

- 2018: USSF 11v11 online module

- 2018: USSF 11v11 in-person module