I don’t do much sports blogging now, but when I do, it’ll be part of Mostly Modern Media at Substack.

Category: Uncategorized

The NWSL, USA Curling and the dangers of inadequate investigations

The accusations of abuse in the NWSL deserved a professional, thorough investigation.

They got that. It’s the Yates Report.

A second report, commissioned by the NWSL and the NWSL Players Association, has some utility. It is, however, flawed in multiple places.

In some cases, dangerously flawed.

As usual, the media reporting on the situation doesn’t help. Everyone from accused sexual predators to coaches who apparently yelled at players are lumped together under the heading “abuse.”

The nuances are important here, and to the investigators’ credit, they ask the powers that be to consider what’s acceptable and what’s unacceptable moving forward. The NWSL doesn’t want any Bobby Knights, nor should it. Players and staff will have to decide if they would abide by a Mike Krzyzewski or even an Anson Dorrance. (“Lost control of her bowels” is a disturbing phrase to describe a fitness test, and “mess with us mentally to pick out who were the weaklings” is a phrase that might have raised a yellow or red flag for the investigators.)

That discussion is all well and good. It’s clear from the report that players have different levels of what they consider “abuse,” and it’s something they should be able to talk through. Absolutely.

Unfortunately, in other areas, the bad guys are predetermined, and the conclusions aren’t always justified.

Consider this bewildering passage concerning Rory Dames. To be sure, there’s no defending his behavior as described here and in the Yates Report unless everyone else involved is lying. But then we get to things like this: “Dames told the investigator that he revoked the media credentials of a player’s boyfriend because he concluded that the boyfriend’s presence was “not positive” based on a conversation with a USWNT coach.”

This point is raised because the NWSL/NWSLPA investigators want to take a US Soccer investigator down a notch for failing to follow up on this “explanation as to the treatment of this player.”

The NWSL/NWSLPA investigators do not, however, take issue with the fact that a player’s boyfriend has a media credential.

Note to journalists: If you start dating a player on a sports team, stop covering that team.

The “guilty until proven innocent — and even then, still guilty” approach isn’t surprising in a sport that holds strict adherence to The Narrative. Players are always right. The lawyers they hired are always right, which is why they get millions of dollars after losing in court. Coaches who cross them — whether they’re perceived as abusive or whether they pull a Tom Sermanni and start tinkering with the lineup — are always wrong. Referees are always wrong. Everyone who has ever worked for the league is wrong. Everyone who was interested in women’s soccer before everyone else got interested in women’s soccer from 2011 onward is wrong.

What’s more disturbing is that the investigators have some fundamental misunderstandings of how to fight abuse. We’ll get to that.

But first, let’s see how someone’s career has been shredded over flimsy, out-of-context conclusions and months waiting in limbo.

James Clarkson

Here are some of the complaints against former Houston Dash coach James Clarkson, who was temporarily suspended for what turned out to be an entire season and will not have his contract renewed.

- “(A)nother said she felt under the microscope based on the position she played and feared she would be cut from the team.” Well, yeah. It’s professional sports. Ask NFL players about their job security.

- The coach thought some players had been drinking the night before a preseason game and that they were hung over. Players deny it. They didn’t deny being out at dinner with a player from the other team until midnight when they had a 6 a.m. wake-up call, or that one of those players became ill.

- A player told a member of the coaching staff but not Clarkson that an injury was bothering her, but she decided to dress because she figured she wouldn’t play. Clarkson, figuring she was fit, put her in the game. She went in and then asked to come out. Clarkson got mad about this, and reports differ on whether he dropped an f-bomb. This is all somehow Clarkson’s fault. (A player who witnessed the incident also said Clarkson later admitted he could’ve handled the situation differently.)

Another note about the last one. On page 71, the report says, “Accounts differ about what happened next.” A player says she doesn’t recall the specific words. On page 104, things are suddenly more certain: “Clarkson denied making this comment, but witnesses corroborated that Clarkson was visibly upset and frustrated at the player, and that the player was upset.”

There’s another passage that paints Clarkson as being a tad racist even though the evidence within that paragraph offers an alternate explanation. Dash player Sarah Gorden, who is Black, said her boyfriend was followed closely by stadium security and told he’d be arrested if he got too close to the team, while white players had freedom to talk with their families. (That’s pretty bad, and we have to hope the team addressed it.) Clarkson asked players to write apologies to stadium security. But upon further investigation, it turns out Clarkson sought those apologies not because Gorden criticized security but because the team had violated COVID-19 protocols.

“But some players and club staff described that Clarkson seemed to defend stadium security, and players and club staff expressed disappointment at Clarkson’s and the club’s failure to attempt to understand the Black players’ perspective. On the other hand, some thought Clarkson handled the situation well and reported that he later expressed his support and apologized if he had appeared insensitive.”

So are the players who reported Clarkson’s support … lying? And the others aren’t? Or, as seems most likely and supported by the evidence, players and staff were disappointed at first but talked through it to clear up any misunderstanding and got assurance of his support?

This incident is lumped together under “Offensive and Insensitive Behavior Related to Race and Ethnicity,” along with accusations that former Washington Spirit coach Richie Burke used the N-word, asked if he should sing the “Black version” or “white version” of Happy Birthday, and compared the team’s poor play to the Holocaust, for which his defense was that he didn’t know there were Jewish players on the team.

Overall, the Joint Investigative Team found that Clarkson committed emotional misconduct.

That’s despite this line: “A majority of players expressed the view that Clarkson’s treatment of players did not rise to the level of abuse or misconduct.”

That’s despite, as the report notes, Clarkson asking for a mental health program to support his players.

That’s despite, as the report notes, Clarkson agreeing that the head coach and general manager should not be the same person.

If you want to fire Clarkson, fire him. Coaches sometimes aren’t that right fit. That’s fine.

But now Clarkson’s name sits alongside that of accused sexual predators and people who don’t seem to care that they use actual racial epithets. His chances of getting another job at this level are surely diminished.

Little wonder he’s fighting back.

It would’ve been far fairer to Clarkson to have fired him months ago. Instead, he was left to twist in the wind for months, only to have his name smeared by trumped-up claims of abuse.

SafeSport and reporting

At the end of a long report detailing how the NWSL and US Soccer failed to investigate NWSL abuse issues, the investigators come up with several recommendations that the NWSL and US Soccer should continue to investigate NWSL abuse issues.

The investigators urge the league to follow through on its 2022 Anti-Harassment Policy to make sure each club has two people, one of which is neither the Board of Governors representative nor the head coach, whose job is to receive reports of potential violations.

Those people are then responsible for reporting these issues to the NWSL.

Ever work in an office in which someone’s sole job is to sit in a swivel chair and relay things from a lower rung of the org chart to a higher rung?

That part is kind of funny. The next part isn’t.

The investigators charge the NWSL with sufficiently staffing its HR and Legal departments to investigate “all complaints of misconduct.”

This is, at best, a bad idea. At worst, it’s illegal.

The US Center for SafeSport, established by federal law (what, you haven’t memorized the Ted Stevens Act yet?), has a SafeSport Code that lists the allegations for which the Center has exclusive jurisdiction (all sexual misconduct, criminal charges of child abuse, various failures to report, etc.) or discretionary jurisdiction (non-sexual child abuse, emotional and physical misconduct, criminal charges not involving sexual misconduct or child abuse, other failures to abide by the Code).

From that Code: “When the relevant organization has reason to believe that the allegations presented fall within the Center’s exclusive jurisdiction, the organization—while able to impose measures—may not investigate or resolve those allegations.”

Continuing: “When the allegations presented fall within the Center’s discretionary jurisdiction, the organization may investigate and resolve the matter, unless and until such time as the Center expressly exercises jurisdiction over the particular allegations.”

Back to the NWSL/NWSLPA report: There’s a claim that “SafeSport only has jurisdiction over reports concerning NWSL coaches or staff who hold U.S. Soccer coaching licenses.” I wonder if that would hold up under scrutiny.

And in that same paragraph: “Many players who spoke with the Joint Investigative Team were not aware that they could report concerns about misconduct to SafeSport. Some within the NWSL held the misconception that SafeSport deals with misconduct against youth athletes and does not investigate misconduct against professional athletes.”

That sounds like a misconception that should be changed. And it may be difficult to do so when we have a report commissioned by the NWSL and NWSLPA that urges the NWSL and its clubs to take the lead.

The Center has had a wobbly start. But it’s just that — a start. The Center is supposed to be like the US Anti-Doping Agency, taking leagues and NGBs out of the business of policing themselves when it comes to drugs. Between the NWSL cases and the horrors of USA Gymnastics, we’ve surely seen enough to know that we need something similar in the realm of abuse as well.

And at the very least, any allegations like the ones against Paul Riley should go to SafeSport. Not someone on the small staff of a professional women’s soccer club.

Finally, let’s consider a recent test case in which the Joint Investigative Team of this NWSL/NWSLPA report investigated something new:

From the report: “In October 2022, the Joint Investigative Team received a report that then-Thorns Head Coach Rhian Wilkinson had disclosed to the Thorns’s HR director potentially inappropriate interactions with a player with whom she had formed a friendship. The Joint Investigative Team promptly conducted a thorough investigation and, based on the evidence, found that Wilkinson did not engage in wrongdoing or violate the Anti-Harassment Policy. On November 4, 2022, these findings were conveyed to the NWSL, NWSLPA, Thorns, Wilkinson, and the player involved. Out of respect for player privacy, this Report does not provide a detailed account of the evidence or findings in this and other instances where the Joint Investigative Team determined no misconduct occurred.”

A few pages later: “The NWSL’s Non-Fraternization Policy, adopted in 2018, states: “No person in management or a supervisory position with a Team or the League shall have a romantic or dating relationship with a League or team employee whom he or she directly supervises or whose terms or conditions of employment he or she may influence.” The Joint Investigative Team found multiple instances of romantic relationships between players and staff members in violation of this policy.”

In her resignation letter, Wilkinson said she and the player had expressed their feelings to each other but stopped it there and went to HR. But other players on the team took issue with the Joint Investigative Team’s work and expressed some misgivings about the whole chain of command:

That letter isn’t mentioned in the report, even though it’s dated November 20, and the report references at least one event from as recently as December 1. Maybe the league didn’t hand it over to the Team?

All of the people involved here are human. NWSL players are human. Lawyers are human. Investigators are human. Coaches are human. We all make mistakes.

What we need is a system that minimizes those mistakes and operates with a clear-headed passion to find the truth while treating everyone — accusers, accused, and those around them — as humans.

Jeff Plush

For my fellow curlers, here’s a quick summary of our former CEO’s appearances in various investigations:

The Yates Report, with which Plush did not cooperate, shows that Plush did a bit to hinder Paul Riley’s future employment within the NWSL after allegations of sexual misconduct were reported. See previous post.

The NWSL/NWSLPA report shows that Plush did a bit more than was reported in the Yates Report, and it says the league failed to act despite Plush’s warnings. However, the NWSL/NWSLPA report relies mostly on one source — Plush, who did cooperate with this one.

Still, the report raises one red flag, and it seems well-substantiated: “Plush told the Joint Investigative Team that the Flash had been considering Riley since October 2015, and Plush warned Lines in October 2015 that the Flash should not hire Riley but should follow up with the Thorns as to why Riley was “no longer coaching there.” Plush wrote that he was “very careful in describing the situation” with Riley because he had been informed by counsel to U.S. Soccer that he could not share the Thorns’s investigative report or its details. However, this position appears inconsistent with the email from the Thorns’s counsel transmitting the Riley report to the League, which Plush received and which did not place any restrictions on the League.”

But the main verdict on Plush is rendered on page 111, and it’s complicated. Plush says he was limited in what he could say about Riley on advice of counsel. The investigators say that’s inconsistent with email from the Thorns counsel and the fact that Plush shared some information with Sky Blue, the New Jersey team that backed away from pursuing Riley. Was it “inconsistent,” or did the advice from counsel come into play after the Thorns email and the Sky Blue conversation?

The bottom line may be how you interpret this final line in his entry on page 111: “By allowing Riley to continue coaching in the NWSL, the League conveyed its continuing implicit approval of him, despite the information Plush received and the concerns that he expressed to others.”

Some people with whom I’ve talked are interpreting “the League” as “Plush.” I don’t think that’s the case, in part because of the “despite” clause and in part because so many other people wielded at least as much power as Plush did. And Riley continued to coach long after Plush was gone.

On the whole, Plush comes across as someone who is too happy to take bad legal advice. That comes up again in the two investigations USA Curling released today. Feel free to ignore the first one, which is only two pages and is essentially a record of the investigator’s inability to get a word with anyone from US Soccer or the NWSL except for one anonymous comment: “Jeff did absolutely nothing wrong in how it was handled.”

The second investigation isn’t much better. It has four interviews — Plush, USA Curling CFO and former USSF/NWSL CFO Eric Gleason, an NWSL team owner, and someone who was a US Soccer official in 2015.

Plush confirms that he didn’t cooperate with the Yates Report on the advice of counsel, and he now recognizes that maybe he should’ve done it anyway. That raises the question of why the Yates Report doesn’t mention him at least saying he had been advised not to cooperate, and it raises the question of why he went along with the NWSL/NWSLPA investigation.

The rest of the USAC investigation casts Plush as a mostly powerless figure, beholden to lawyers and USSF officials, who did what little he could to stop Riley from being hired at an NWSL team. I covered women’s soccer during that time (and many years before and after), and I know there’s a lot of truth in this depiction. But at best, Plush is following various lawyers over a cliff. A good leader should know better.

Other than that, the investigation is flimsy. The only interviews are with Plush and people sympathetic to him.

To recap what’s happened since then: Plush resigned, as did the board chair and two other board members.

And the new management isn’t pleased with these investigations:

“It was important to engage a third-party to do this work, but the quality of these reports does not rise to the level that the Board and the curling community deserved,” noted USA Curling Board Chair Bret Jackson. “As a result, we will conduct an audit of our internal process, and learn how we can be better in the future.”

So what does this mean for USA Curling moving forward?

In social media, a few people want to see the rest of the board resign as well. I’ll disagree for two reasons:

First, the decision to keep Plush (before he resigned) doesn’t appear to be unanimous. Three days after the board announced he was sticking around, the Athletes Advisory Council issued a carefully worded statement that left the door open for further consideration. Plush resigned 12 days later, closely followed by the board chair and independent directors. It’s fair to say they didn’t just find a burning bush that told them to change their ways. Someone gave them a push behind the scenes.

Second, it’s easy to see how board members could have been misled into thinking Plush did nothing wrong. When an investigator hands over interviews with top soccer people defending him, it’s all too tempting to take that as face value. Failing to see beyond the investigator’s report is a mistake, not an act of malice. And in a sense, the investigator and the interviewees were right. He did “nothing wrong.” It’s just that, after a certain point in the timeline, he did nothing at all. It takes a bit more digging to realize his inaction was based on an unwillingness to stand up to people giving him bad advice.

So the top officials at USA Curling are gone. The new board chair and interim CEO have thrown open the discussion to see how USAC could do things better.

A National Governing Body (NGB) is vital to the success of any Olympic sport. In my next post, I’ll explain why that’s the case and why I’ll continue to be a USAC member even though I’m hardly national championship material.

Appeals court lets travesty stand, leaving soccer trainer in prison

Maybe their hands were tied. Maybe they couldn’t hold the overzealous prosecutors, prodded by influential snowplow parents (snowplows are indeed useful in upstate New York), responsible for soccer trainer Shelby Garigen’s plea deal.

In any case, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals snuck a decision past me in late January, deciding they didn’t need to take a real look at the shenanigans that landed Garigen in jail because she was planning to have sex with someone of legal age in New York but made the mistake of getting him to send nude pics to her.

Here’s the decision:

A few points:

Specific assertions the appellate judges addressed

The judges first say these points don’t fall “within the ‘very circumscribed’ exceptions to the validity of an appellate waiver,” so they’re already setting a high bar to clear.

Point 1: Because the meetup (which proved to be a setup to arrest Garigen) and the sentencing took place after the person in question turned 18, Garigen’s appellate lawyer argues that the person in question should’ve been the one speaking, if he so chose, at Garigen’s sentencing. Instead, his parents spoke. Rephrased in the appellate ruling: “(Garigen asserts that) the parents of a victim (“Victim 1”) made false and biased statements against Garigen and should not have been allowed to speak at her sentencing.” The father’s theme continued when he offered his apparent expert opinion on appellant’s psychiatric diagnosis.” Garigen’s lawyer: “First, Victim 1’s father is not a psychiatrist.”

The appellate court says the lower court was within its rights to hear the parents of the “victim” (again, a legally consenting young man who wanted to have sex with an older woman) as long as Garigen was able to respond at the sentencing. They do NOT address, as far as I can see, the question of whether the father of the “victim” should have been allowed to offer expert opinions on Garigen’s mental health. Nor do they address the topic of whether a more competent lawyer would have offered a more robust response.

Re-phrased by the appellate court as “(Garigen asserts that) Victim 1’s father had improper control over the prosecution of Garigen’s case.” The father is a former prosecutor who has worked on cases of sex crimes. (The mother works for the Erie County DA’s office.) Garigen’s appeals lawyer: “The father advised the court that he ‘helped the U.S. Attorney’s Office prosecute this case.’”

The appellate judges say the record doesn’t support Garigen’s claims. They do not support their assertion.

Garigen’s lawyer further argues that the father’s words imply that he had read the Presentence Report, and that document is supposed to be read only by the court and respective counsel.

The appellate judges wave this accusation away, not convincingly, taking a statement out of context from the 28th paragraph of Garigen’s appeal.

What the appellate judges didn’t address

Given their insistence that there’s nothing to review here because Garigen should’ve known the risks of accepting her plea deal, it’s not surprising the appellate judges didn’t address the fact that the parents of the “victim” presented several arguments that are, in fact, hogwash.

From what I’ve written before: The parents claim their son has fallen out with a friend who was also 17 when he sent pictures to Garigen, and they say that’s Garigen’s fault. Garigen’s lawyer retorts: “(The mother) fails to note the real possibility that her 17-year-old son may have withdrawn from friends and family because the FBI became involved by interviewing both him and his friend, Victim 2. Notably, Victim 2 declined to provide a Victim Impact Statement and requested no further law enforcement contact.”

And: The parents, in the characterization of Garigen’s lawyer, focused on Garigen “luring” their son — again, a consenting adult — to have sex. They don’t harp on the fact that the only charge she faces, “child pornography,” is the direct result of their son sending her dirty pictures.

Again, perhaps those aren’t questions for the appellate court to address.

I find it hard to believe, though, that this argument should be ignored:

Garigen’s lawyer draws a distinction between pictures a young man posts to Snapchat and what we would normally call child pornography: “Sending a self-picture of an ‘unidentified’ penis (i.e., Victim 1’s face was not in the picture) to a self-deleting application would not in any way ‘create a market’ for child pornography and contribute to the victimization of minors.”

In other words … the entire basis for the prosecution of this case may have been built on a misapplication of the law.

If that’s not in the appellate court’s jurisdiction, it should be. If the appellate court can’t do more to right wrongs that were done because Garigen’s original lawyer failed to object in time, that needs to change. Time to rewrite some laws in New York.

We all know what happened …

- A teenager of consenting age started flirting with his trainer, and things progressed to where they started talking about having sex and eventually agreed to meet up for that purpose.

- The teenager’s well-connected parents got wind of it and refused to assign any responsibility to their kid. All her fault, they decided.

- A terrified, ill-informed woman took a plea deal but hoped for a reasonable sentence.

- Those well-connected parents took advantage of their connections to bulldoze her lawyer.

- An 80-year-old judge barely took the time to consider the motion by her replacement lawyer.

Maybe the appellate court can’t address it. It’s a pity we don’t have more watchdogs in the media who can get to that courthouse, the FBI’s Buffalo office and the U.S. Attorney’s office to ask if it’s really necessary to take up prison space for this. Probation? Sure. A ban from working in soccer? Already happened. But prison? I’m sure taxpayers are thrilled.

I’ve asked before if anyone wants to comment on this case. I’ll do a follow-up post if so.

Previous posts:

- Oct. 8, 2020: A sexist double-standard in sexual abuse cases?

- Feb. 21, 2021: Why is a New York court obsessed with putting a trainer in prison?

- Oct. 17, 2021: Still waiting for justice in soccer sexual abuse cases

And meanwhile …

More than five and a half years after his arrest, Juan Ramos might finally be forced to go to court to answer the allegations that he began a sexual relationship with a player when she was 13. Maybe the court date is set for April 11 at 9:30 a.m. in Room 4810 of the Broward County Courthouse.

I say “might” because Ramos already managed to skate by when he and his counsel, Kevin Kulik, were no-shows at a calendar call in October. A capias warrant was issued, but Kulik won the day with the “we didn’t know” defense.

So this document doesn’t instill confidence:

If you have a sharp eye, you may notice that the 500 S. whatever in Fort Lauderdale is not the address Kulik listed on his “my client and I didn’t know” brief. That was 1293 North University Drive #204, Coral Springs, FL.

That’s the address of a UPS Store. I’ve verified that his office is in that store.

One thing Ramos and Garigen have in common is that they’re listed as “ineligible” in the SafeSport registry. They may never work in soccer again — assuming people do the most basic of background checks. And that’s fine.

But there’s no question which crime is less serious and which crime has been more seriously prosecuted. And they’re not the same one. Juan Ramos has been walking around free since the Obama administration, and Shelby Garigen is in prison.

New in the SafeSport registry …

As long as I’m checking, here are the latest names added to the database. Maybe I’ll end up investigating some of these as well.

Disclaimer: There is, of course, the minute chance that there are two people with the same name and the same town, one of whom was arrested and another of whom is in the SafeSport registry. I’ve taken extra care in a couple of cases as mentioned below. In other cases, I think the chance of mistaken identity is virtually none, and even if that were to happen, the people in question were either in the SafeSport registry or facing criminal charges.

March 28: Martin Pantoja, San Mateo, Calif. — Criminal Disposition — Sexual Misconduct; Criminal Disposition — involving a minor. Ineligible (subject to appeal). Pantoja was arrested in February. I found one Martin Pantoja in San Mateo but I’m not linking here just in case there are two Martin Pantojas of roughly the same age in the area.

March 25: Jonathan Ledesma, Highland, Calif. — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Suspension. Arrested March 17; charged with numerous counts of sexual assault on a minor. Police say he started coaching her at age 9 in AYSO.

March 24: Kristen Wessel, Colorado Springs, Colo. — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Suspension. Court date April 28. Charge is listed as a felony count of “failure to comply.”

March 24: Allan Hilsinger, Cincinnati, Ohio — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Suspension. Arrested in March on two counts of gross sexual imposition involving a 10-year-old girl.

March 18: Timothy Harrison, Babylon, N.Y. — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Suspension. A Timothy Harrison of Babylon was arrested in March over an alleged sexual relationship with a minor in 2013, but the stories list him as a special ed teacher who coached lacrosse and basketball, which raises the question of why U.S. Soccer and not the other sports federations are listed with that name in the SafeSport database. If it’s the same guy, then he should also be suspended from the other sports.

March 16: Dennis Doyle, Beaverton, Ore. — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Suspension. Doyle founded a club called Westside Metros and was still vice president of the since-renamed Westside Timbers until he was arrested on child pornography charges. He was also mayor of Beaverton for 12 years.

March 10: Eric Eskelsen, Blackfoot, Idaho — Criminal Disposition. Permanent Ineligibility. I didn’t find anything about him.

March 7: Evan Thornton, Mount Pleasant, S.C. — Criminal Disposition — Sexual Misconduct; Criminal Disposition — involving a minor. Ineligible. Substitute teacher and soccer coach was arrested in December on charges of unlawful sexual activity with a 16-year-old student. He was a varsity high school coach before age 23 for some reason.

Feb. 28: Walter Jones III, Roseville, Calif. — Criminal Disposition — Sexual Misconduct; Criminal Disposition — involving a minor. Ineligible. I didn’t find any details. There’s a Walter Jones arrest listed in the Placer County inmate records, but if it’s the same guy, the only thing the records add is that he’ll have a May 11 court date.

Feb. 28: Ian Ebert, Irvine, Calif. — Criminal Disposition — Sexual Misconduct; Criminal Disposition — involving a minor. Ineligible. An Irvine coach by that name was arrested in 2013, so that’s either a belated addition to the database or an astounding coincidence.

Feb. 14: Rory Dames, Oak Brook, Ill. — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Restrictions: Coaching / Training Restriction(s), Contact / Communication Limitation(s), No Contact Directive(s). You may have heard of this one.

Feb. 9: Eduardo Pinuelas, El Paso, Texas — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Suspension. No Contact Directive(s). I’m checking to try to match up a name I found.

Jan. 20: Amilcar Velasquez, no city listed — Criminal Disposition — involving a minor. Permanent Ineligibility. I found a soccer coach by that name, and I found someone by that name who was arrested, but they’re thousands of miles apart.

Jan. 10: Dylan Cline, no city listed — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Restrictions: No Unsupervised Coaching / Training, Contact / Communication Limitation(s), Travel / Lodging Restriction(s), No Contact Directive(s). There are several Dylan Clines out there.

Jan. 7: Brian Kohler, Warsaw, Ind. — Allegations of Misconduct. Temporary Suspension. No Contact Directive(s). Didn’t find details.

I hope people take an interest in this. The pro coaches understandably get the publicity. But while the names above represent a tiny percentage of the people involved in youth soccer, these cases deserve scrutiny. Of all parties.

Originally published at http://mostlymodernmedia.com on April 5, 2022.

Promotion/relegation 2022, by popular demand (sort of)

Apologies for misleading people with the headline. I’m not saying promotion/relegation is going to happen because of popular demand. The growth in MLS and other “closed” leagues is a rather powerful argument against that argument.

No, I’m doing a post by popular demand. Also because MLS is growing too much, moving up to 30 teams and a Leagues Cup competition with Mexico.

So yes, it’s time to reconsider. First, I’ll need to sum up the thousands of words I’ve written on the topic, much of it on my own blogs but also occasionally in outlets like The Guardian. Bear in mind that if you want a good synopsis of how U.S. soccer arrived at this point, I wrote the book on the subject:

It only mentions pro/rel in passing, but the “historical and cultural reality check” is relevant. People often say “pro/rel works everywhere else, so why not here?” without considering what makes the USA unique and difficult.

A quick look back at the issue:

- A little outdated: A look at the major players in professional and elite amateur soccer.

- The pros of pro/rel

- The cons of pro/rel

- A refutation of the idea that pro/rel necessarily leads to better player development

- A 2017 promotion/relegation plan (along with a look at pro/rel myths)

- A 2018 plea for a reset of the discussion

Yes, I’ve written plans for pro/rel in the past. And given the Leagues Cup and growing intermingling with Mexico, I think these plans need a rewrite.

I already wrote a suggested league(s) calendar to accommodate the Leagues Cup. It’s at Soccer America.

So let’s go farther. This might seem unusual, but bear in mind that a lot of countries (see England, Japan and the Netherlands) have historically had narrow gateways between amateur and pro divisions. Also, Brazil had one year in which the final 16 teams included qualifiers from the lower divisions.

The goal here is simple: Maximize opportunity, minimize risk.

Start with a licensing requirement based on facilities, staffing, academy and competitive criteria. Instead of joining MLS as an expansion club, an existing club obtains a MLS license, with which they’re guaranteed a place in either the first or second division. Other clubs can get an MLS associate license, which guarantees a place in either the second or third division. The third division can grow almost indefinitely through independent leagues with their own competition rules. If you really want to have pro/rel within a third-division league, fine.

So here’s the deal:

Fall season

Late July (as soon as practical after World Cup or other international tournaments) to mid-December, 20 weeks plus playoff final. Also note CONCACAF Champions Cup.

MLS Division 1: 16 teams, all with full licenses. East/West divisions. Top four in each qualify for Leagues Cup and cannot be relegated. Top team in each division qualifies for single-game MLS Cup at warm-weather neutral venue just before Christmas.

MLS Division 2: 16 teams, full or associate licenses, with room to grow. Four teams qualify for Leagues Cup. Those with full licenses are promoted.

Third division: Independent leagues that govern as they see fit.

Spring season

February to mid-May (finished in time for World Cup/other international tournament). Also note Open Cup.

Leagues Cup: 12 MLS, 12 Liga MX. Four-team single-elimination playoff.

MLS Promotion Cup: All full-license clubs that aren’t in Leagues Cup play for spots in MLS Division 1.

Third division: Independent leagues continue, with associate-license teams rejoining. National tournament of qualified teams determines which teams play in Division 2 the next season.

Other tournaments

CONCACAF Champions League (really Cup): Knockout tournament in fall but give byes to quarterfinals to Leagues Cup, MLS, Liga MX and CONCACAF League champions. Play-in round spots go to runners-up of those competitions, CONCACAF League third-place finisher, Caribbean champion, U.S. Open Cup winner and Canadian champion. (If someone qualifies for the play-in round by two different routes — say, Open Cup winner and MLS runner-up — that team gets a bye. If any other spaces remain, go to third place finisher in Leagues Cup.)

U.S. Open Cup: Local leagues and third division play qualifying rounds in fall. In mid-January, surviving teams face MLS teams (excluding League Cup teams) in 20 four-team groups at warm-weather sites. That takes us to 32 teams for knockout tournament culminating in May final.

The rationale

Existing MLS clubs face little risk to the nine-figure investments they’ve made. Every year, they have a chance at the Leagues Cup. They’ll either have a chance at MLS Cup or promotion.

Up-and-coming pro clubs get a new pathway that could see them reach the second division and even the Leagues Cup, in addition to the Open Cup. Over time, they may solidify and earn a full license.

Other pro clubs can play in regional leagues. Over time, they may earn an associate license.

Youth players will have opportunities with local clubs that cannot lose pro status unless they collapse. You won’t see an entire state’s kids lose their pathways to the pros just because the senior team had injury problems and got relegated.

And it’ll be fun.

And it’ll never happen.

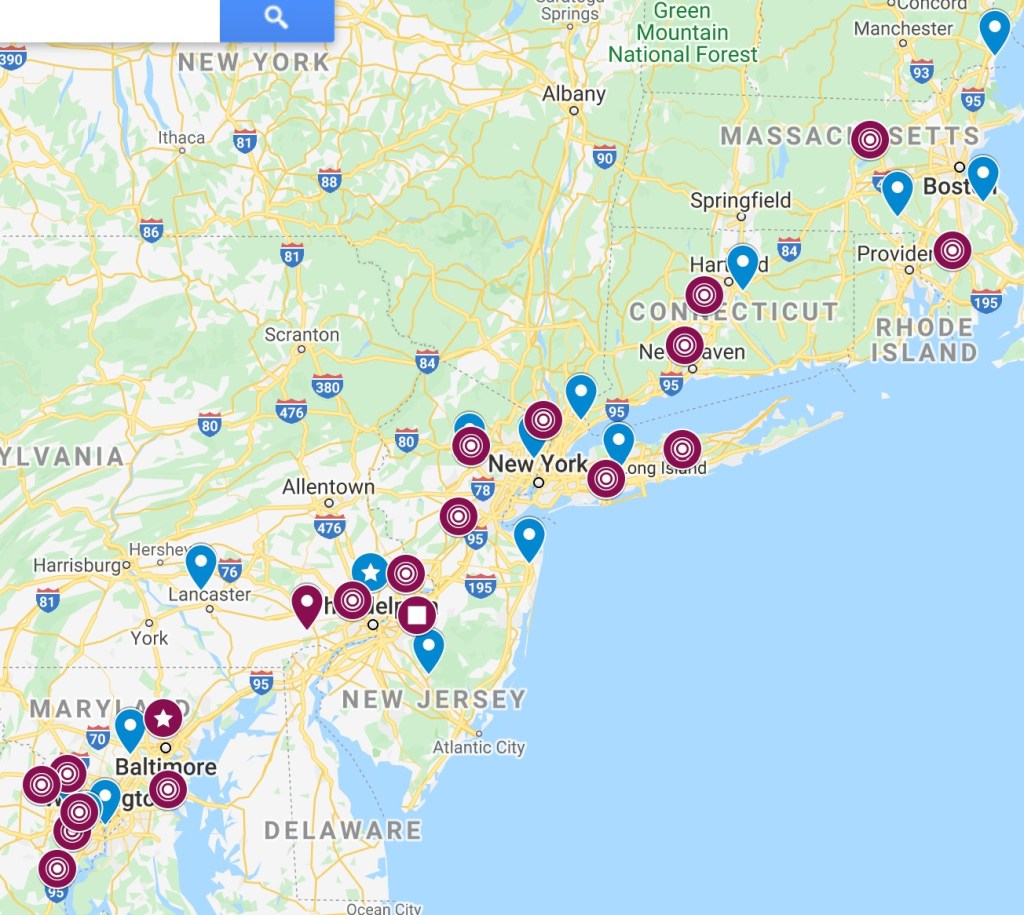

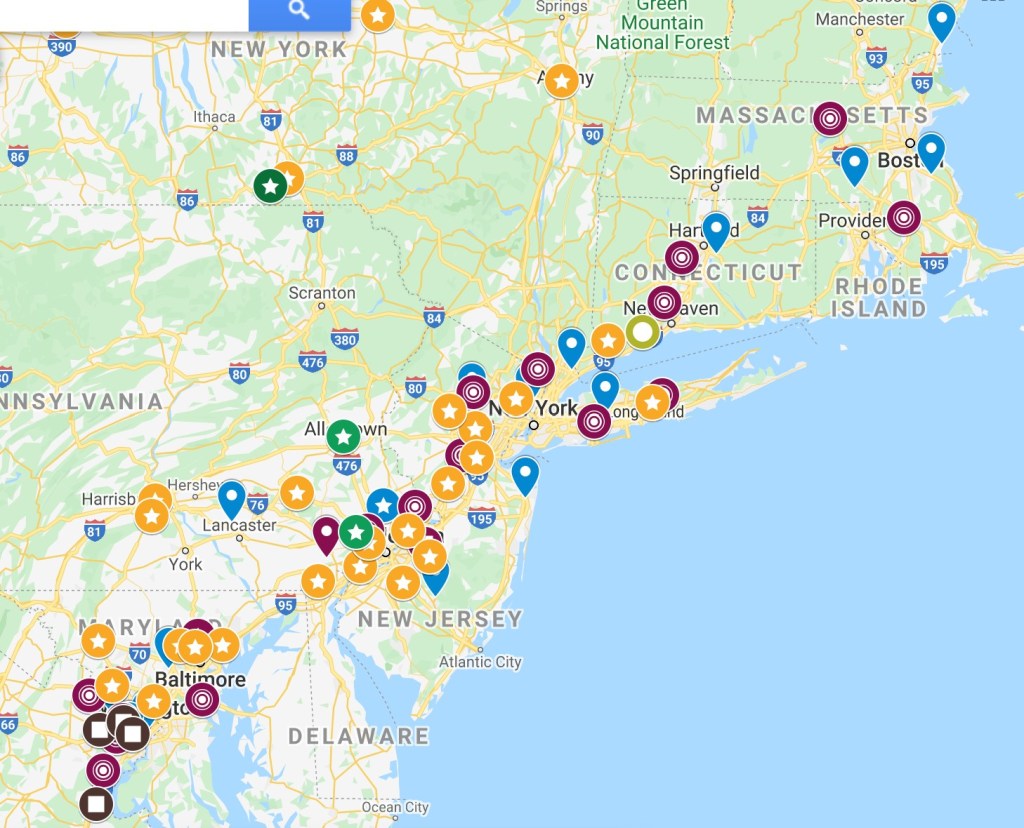

Maps

Legend:

The map represents each club’s top level of competition in 2019-20 except for USYS NL 19, which is 2018-19. Some clubs may have second teams, third teams, ninth teams, etc., in lower leagues.

To be listed on this map, clubs have to meet one of the following criteria:

- Development Academy (DA), 2019-20

- ECNL, 2019-20 and/or 2020-21 (“Carryover” means the club is remaining in the ECNL next year.)

- ECNL Regional Leagues, 2019-20 and/or 2020-21

- Girls Academy, 2020-21.

- U.S. Youth Soccer National League U-17 age group, 2019-20 or 2018-19 (USYS NL, USYS NL 19). This league’s composition changes each year based on qualification.

- At least one team in the age groups U-14 and above ranked in the top 50 at youthsoccerrankings.us.

USYS regional = U.S. Youth Soccer conferences. Again, composition changes each year based on qualification. Not every club from this level is listed — only the clubs that placed a team in the Top 50. (For clubs moving to GA, I haven’t specified whether a club was in the National League or regionals — they’re just categorized as “USYS” on the map.)

NPL = National Premier Leagues. Some of these have become ECNL regional leagues.

Local = Not in any of the leagues above. Local leagues aren’t necessarily weaker than NPLs, and some leagues have similar travel demands to those leagues. (For example: The Club Champions League, which includes Beach FC (Va.), has teams in the D.C. suburbs, Roanoke and Virginia Beach, all drives of 3 1/2 to 4 1/2 hours even on those rare days with no traffic.)

Map closeups:

English clubs in danger of collapsing early in the season — why?

I can’t claim to be an expert on the “winding-up” of soccer clubs. In my experience, every time it’s imminent, something magic happens to stop it.

Something feels different this time for two clubs, in part because of the timing. We’re just a couple of weeks into the season. Could we really see League One reduced by two, like WPS in 2010 or some indoor soccer teams back in the 2000s?

That’s not supposed to happen in England, is it?

As it stands now, the clubs in question have a combined -23 points. Not -23 goal difference. They’ve each had 12 points deducted. Bolton managed a draw in one of their four matches. Bury have yet to play at all.

Congratulations to Southend United, who have lost all five matches so far and still have an 11-point gap ahead of the bottom two places. AFC Wimbledon, the poster child for phoenix supporter-started clubs, has 1 point and is out of the relegation places.

Bury’s Twitter feed now has a call for volunteers that radiates English charm:

Bury were in trouble last year but were bailed out by Steve Dale, a businessman whose “business record appeared to consist largely of buying failing companies, selling their assets and seeing them liquidated or dissolved,” The Guardian reports.

The EFL suspended Bury’s fixtures to buy them time. We’ll see what happens this week. The club supposedly faces a Tuesday deadline to conclude a sale.

While Bury haven’t been in the top flight since WWII, Bolton’s history is distinguished, having spent most of their history in the top tier and playing in the UEFA Cup twice in the 2000s. But they’re in the same situation today, facing a Tuesday deadline to sort things out.

I’d offer an explanation, but I don’t have one. Are clubs spending wildly in an effort to climb the ladder? Does the Premier League simply take up all the available bandwidth?

The official Athletes(‘) Council arrivals and departures list, and more

I got clarification on one thing from the past post on the Athletes Council (or Athletes’ or Athlete’s, though the last seems incorrect unless you’re talking about one athlete).

Elected/re-elected in 2016 to 2017-21 term (not up for election this time)

Gavin Sibayan (Paralympic)

Brian Ching (MNT)

Brad Guzan (MNT, playing for team as I type)

Stuart Holden (MNT)

John O’Brien (MNT)

Jonathan Spector (MNT)

Lauren Holiday (WNT)

Lori Lindsay (WNT)

Heather O’Reilly (WNT)

Aly Wagner (WNT)

So that’s five MNT, four WNT and one Paralympic.

Running for re-election

Chris Ahrens (Paralympic)

Carlos Bocanegra (MNT)

Lindsay Tarpley (WNT)

Nick Perera (Beach)

Not returning (either term-limited, out of 10-year window or, like Jerry Seinfeld, choosing not to run)

Shannon Boxx (WNT)

Angela Hucles (WNT)

Leslie Osborne (WNT)

Kate Markgraf (WNT)

Christie Rampone (WNT)

Will John (YNT)

So the WNT might not have half the seats on the Council in the next two years as it did in the past two years. Then again …

Candidates

Sean Boyle (Paralympic)

Kevin Hensley (Paralympic)

Landon Donovan (MNT)

Yael Averbuch (WNT)

Meghan Klingenberg (WNT)

Ali Krieger (WNT)

Samantha Mewis (WNT)

Alex Morgan (WNT)

Alyssa Naeher (WNT)

Becky Sauerbrunn (WNT)

McCall Zerboni (WNT)

Jason Leopoldo (Beach)

So when you add in the candidates for re-election, the breakdown is:

3 Paralympic

2 MNT

9 WNT

2 Beach

The WNT will get at least three seats, even if all seven of the non-WNT candidates win. The possible breakdowns coming out of this election are:

1-4 Paralympic

5-7 MNT

7-13 WNT

0-2 Beach

0 Futsal

0 YNT

Plenty of overlap with the YNT, of course — almost all MNT/WNT players were on the YNTs at some point, as was Leopoldo.

Note that the election process has no guarantee of diversity. It certainly could end up with 13 WNT players/alumni. Or four Paralympians. The chair and vice chair positions have had an even MNT/WNT/Paralympian split in recent years, but that’s not required.

The Council could be more diverse than it currently is. I found a few examples of people who are eligible from their YNT days (as Will John was). It’d be interesting if the MASL ever joins U.S. Soccer and one of its many players from the futsal national team runs.) Like all aspects of U.S. Soccer, it’s getting more scrutiny. It now has a website and is posting its policies and processes.

The most controversial inclusion, on the current board or the nominees, is Carlos Bocanegra, who’s now in a management position with an MLS team. Ethics hounds would probably have a good argument on whether that’s a conflict of interest.

That said, repeat after me …

The Athletes Council is not a union. It does not negotiate with “management.”

You could argue that Bocanegra isn’t well-placed to represent athletes in his current role — or simply that there are other people better suited to do so.

But they still need more people running.

Moving forward and making peace with U.S. Soccer’s “change” wing and the Athletes’ Council

I have an important message for the “Gang of Six” supporters:

You made a difference. Really. Your choice now is whether you want to follow through or just take to Twitter and whine about the election result.

Having spent 48 wild hours in Orlando, I think people in U.S. Soccer are receptive to change. Maybe not the specific solution you want, maybe not at the pace you want. Maybe not with the fiery rhetoric you want. But they’re open to it.

Having spent 48 wild hours in Orlando, I think people in U.S. Soccer are receptive to change. Maybe not the specific solution you want, maybe not at the pace you want. Maybe not with the fiery rhetoric you want. But they’re open to it.

And yes, that includes the Athletes’ Council. They could’ve done things differently, and I’ll get to that. But you can’t write them off just because they voted for an “establishment” candidate (who has only been VP for two years and was an independent director before that).

I realize this post will seem a little pedantic. While in Orlando, someone with one of the campaigns sent me an angry email saying I act like I know everything. But in that discussion, the only things I needed to know were (A) the hotel layout between the sports bar and the Unicorn meeting room, (B) what Sunil Gulati looks like and (C) what Don Garber looks like. And the things I’ll say here are, frankly, just as obvious as those things. As Edie Brickell sang: I know what I know, if you know what I mean.

I’ll dispsense with the preachy stuff early and then move on to some actual ideas …

1. Drop the nonsense and get educated

This isn’t just directed at Soccer Twitter and the conspiracy theories of doom. Certainly a bunch of bro/rel dudes should spend most of this Lenten season atoning for everything they said about Kathy Carter, Julie Foudy, Chris Ahrens, Carlos Bocanegra, Sunil Gulati, Don Garber, Nipun Chopra, Kyle Martino, Donna Shalala …

Then consider the sheer ignorance of this BigSoccer post on Carlos Cordeiro: “He was the VP under Sunil during the biggest disaster in the history of US Soccer.” You may have 100 legitimate questions and concerns about the new president. Blaming him for the men’s national team World Cup flameout is a flying leap across the giant atrium in the Renaissance hotel.

Some of the campaigns deserve a bit of blame for the cesspool surrounding the election as well. Consider this non-hypothetical: Given the couple of inevitable last-minute changes to state representation, when U.S. Soccer sends out a list with those changes to candidates, do you (A) thank the staffer who had to dig that up and send it out or (B) go on Twitter to put the federation on blast for telling you these things so late in the campaign, as if it’s a conspiracy rather than an additional level of transparency?

And behind a lot of it is the NASL and its legal challenge against U.S. Soccer, a suit for which I didn’t detect a lot of sympathy in Orlando. It’s gone way beyond fussing with Gulati and Garber. They’ve sued most of the board, and by extension, they’ve thumbed their noses at everyone who elected the board. It’s funny, but a bunch of people who’ve spent much of their adult lives volunteering in the sport don’t take too kindly to being sued by someone who bought the New York Cosmos a year ago and now wants to dictate how professional soccer should be run.

The NASL certainly has a big overlap with the more radical (or factually impaired) wing of Soccer Twitter. And what has it gotten them? A bunch of lawsuits and a plan to prop up D2 by bringing up some NPSL teams.

As promised, there’s another way forward …

2. Work with the states

You may not be able to walk into an Eastern New York adult soccer meeting and walk out as Sal Rapaglia’s replacement as president. Other states, best represented in Orlando by West Virginia’s ebullient Dave Laraba, have openly asked for some new blood.

Even if you can’t get onto a state board, try to work with them. Attend their meetings.

You’ll find many of them are receptive. Yes, Carlos Cordeiro and Kathy Carter combined for a little more than 70 percent of the vote. But we know who many of those voters are. The athletes. The Pro Council. U.S. Youth Soccer, which has a handful of organizational votes as well as being the umbrella group for state associations, endorsed Cordeiro.

Take them out, and you have a bunch of state associations who were clearly split all over the place.

And — this may shock some of you — for some of them, Cordeiro is the “change” candidate.

He’s not Sunil Gulati. If you saw the board meeting Friday in Orlando, you saw a president who, for all his accomplishments, didn’t seem too interested in listening. Cordeiro is the opposite. I actually have a hard time picturing him presiding over a National Council meeting, but they’ll figure it out.

(For that matter, Kathy Carter isn’t Sunil Gulati. But the manner in which she entered the election drew a lot of legitimate questions, as did her campaign-killing idea to have Casey Wasserman oversee an “independent” commission despite his agency’s deep ties to so many players. She is a “soccer person” in every sense of the phrase. This just was not the right election for her.)

The states, and perhaps some national organizations, are where you can gain momentum for this …

3. Suggest bylaws and policies

Toward the end of the big meeting Saturday in Orlando, Cal South president Derek Barraza stepped up to the microphone with a reminder for his fellow National Council members: We’re not just here to vote. We’re here to do our duty and make policy.

That’s not just academic. If you’ve read my recaps of meetings gone by, you’ve seen bylaws and policies suggested by various parties and approved by the memberships. Louisiana Soccer Association. Bylaw/policy machine Richard Groff. A task force on professional player registrations. Eastern New York Youth Association (not the adults). Athletes’ Council chair Jon McCullough. A policy from a Transgender Task Force.

You may think people in power aren’t listening to such things. The voting records suggest otherwise. And even the weekend’s symbolic effort to cut registration fees in half (something no right-minded person was going to do just before electing a new president who may have another mandate to use or reduce those fees) wasn’t just spitting into the wind. In the board meeting, Athletes’ Council chair Chris Ahrens asked several good questions about how to proceed on that matter. You can bet this issue will come up again.

So along these lines, let’s try this:

4. Lobby to change the Professional League Standards

It’s safe to say promotion and relegation in the pro leagues is not an issue that moves the masses among the U.S. Soccer membership. They’re not necessarily opposed to it — Kyle Martino had support among states and was one of three finalists for the Athletes’ Council votes — but it’s not their top priority. Frankly, there’s no reason it should be. (For reference, see everything I’ve written on the topic.)

The way to get that going isn’t to elect Eric Wynalda president. It’s not a lawsuit or a grievance, where any “victory” would have us racing to find the correct spelling of “Pyrrhic.” Peter Wilt has the right idea — start building toward pro/rel within the lower divisions. If it catches fire and makes MLS owners realize they should be part of it, great. If not, at least you’ve reinvigorated the lower divisions and given more people more opportunities.

The muted response to NISA suggests to me that what I’ve seen for the last 22 years hasn’t really changed — owners have found it’s a lot simpler and cheaper to run a summer amateur team than it is to run a full-season pro club. But aside from pesky things like “workers comp” and “salaries,” there’s one legitimate obstacle keeping clubs from organizing new D3 leagues: the Pro League Standards.

Standards exist for a reason, of course. U.S. Soccer has an interest in making sure its pro leagues are credible. A $250,000 performance bond to make sure a team can make it through a season is certainly reasonable, as are some (maybe not all) of the requirements on fields, stadiums and staffing. (Can we please drop the “media guide” requirement? Are those still printed?)

The big one is the “individual net worth” requirement. Perhaps a legal or economic authority can explain otherwise, but I’ve never understood why a pro club requires one person to have $10 million. If you have people who can put up the performance bond — perhaps even an increased bond — why would it matter whether the group can find an owner who’s in the top 1 percent?

The big one is the “individual net worth” requirement. Perhaps a legal or economic authority can explain otherwise, but I’ve never understood why a pro club requires one person to have $10 million. If you have people who can put up the performance bond — perhaps even an increased bond — why would it matter whether the group can find an owner who’s in the top 1 percent?

Can the standards be overturned from within? I think so. At the very least, you can force people to vote yay or nay on the record, which is something you can use in future presidential campaigns and might be more useful than a conspiracy theory.

And there’s one group that really should be interested in such things …

5. Reach out to the Athletes’ Council

This group took a lot of unfair abuse over the past week. First, they were accused of being pawns for Kathy Carter. It was fun to see the conspiracy theorists try to adapt when the athletes announced they were going as a bloc for Cordeiro. It was also fun to see Hope Solo lecture them about not reading bylaws when she demonstrated little grasp of the published election procedures and a few other simple bits of public info. (Again — coaching modules aren’t age-appropriate? Where’d she get that?)

But we still don’t have a good grasp of what issues they were considering. In talking about Cordeiro, they mentioned his experience — which is a legitimate qualification — and Carlos Bocanegra said he felt the candidates’ platforms were similar and vague, which was partially true.

It would be reassuring, though, to hear that the athletes are concerned about the grassroots. Perhaps it’d be nice to hear they’re going to work in concert with states.

And changing the Pro League Standards should be something that would appeal to the athletes. It’s more opportunity, isn’t it?

So look, reformists (genuine reformists, not people who’ve staked their identities on pretending they understand pro/rel while ignorant Americans do not), you have opportunities. One well-connected source told me he thinks we’re going to have fewer unopposed elections down the road.

Change is coming. As it stands now, the federation has voted for incremental change. Maybe if people can push for a few more incremental changes, we’ll be able to look back in a couple of years and see if it all added up to something big.

Best of SportsMyriad 2014

The best-read posts and the most-overlooked posts of the year. (In other words — what you read and what I’m still attached to even though you didn’t read it, so in the spirit of the holidays, please give it another chance!)

BEST-READ (not counting the 2014 medal projections and all related posts, which destroy all, and not counting 2012’s Single-Digit Soccer: Flunk the 2-3-1?, which still gets traffic)

5. Women’s soccer: Show me the money: Building off Allison McCann’s piece on NWSL salaries and her ill-timed piece on Tyresö.

4. Wrong time to suspend Hope Solo: If nothing else, I confused people who think I wish nothing but ill on the USA’s controversial keeper.

3. Washington Spirit vs. FC Kansas City: Goal rush: An early game for the Spirit and an atypical game in retrospect, rolling over the eventual champions with a first-half surge instead of waiting until Minute 90something to conjure up an unlikely result.

2. Single-Digit Soccer: Give U10 travel the boot: This will be one of the big issues in my book.

1. Remembering Dan Borislow: Once the shock of the news passed, I wrote a remembrance of the former WPS magicJack owner that I hope captured his complexities.

(Hey — no pro/rel posts!)

MOST OVERLOOKED

MLS, USA and Canada 2022: One vision: A few offbeat suggestions for soccer’s future along with a couple of current trends. And Peter Wilt as FIFA president.

NWSL: Spirit, Breakers and the end of reality: One of the craziest women’s soccer games of the year.

An offbeat proposal for NWSL 2015: Solving the scheduling dilemma.

MLS: Time to quit playing hardball: Written nine months before the CBA talks really got underway.

UFC, MLS, markets and monopolies: Why the MLS lawsuit is a bad precedent for the fighters now suing the UFC.

Why I prefer the Olympics to the World Cup: Really. Includes a good John Oliver clip.

College athlete unions, paying players and unasked questions: Not just picking a fight with Jay Bilas.

‘Enduring Spirit’ epilogue: Thoughts from Diana Matheson: Hey, she was nice enough to respond to my postseason questions. Read them!

U.S. Open Cup: Top 14 teams and upset history: See the spreadsheet!

Break up the Olympics: Let all four U.S. bid cities host the Games.

War on Nonrevenue Sports returns: USOC gearing up: Has anyone noticed that sports other than football and basketball are endangered on college campuses?

STUFF I WROTE ELSEWHERE

A little knowledge on the USA TODAY layoffs: Essentially a pointed rebuttal to some guy who thought he knew what was going on.

Weird Al-related question: Lamest claims to fame: In which I point out my strange connections to everyone from Kim Basinger to George Will to Ben Folds.

Why we believe utter crap: Political scientist Brendan Nyhan has figured it out.

Leon Sebring Dure III: 1931-2014: My father’s life as a Marine, designated hitter opponent, survivor, and man who showed his love for the world with a sense of responsibility.

In defense of the Spin Doctors: Seriously.

Farewell to Landon Donovan: My memories of covering the legend.

Most Essential Simpsons Episodes of the Last 5 Seasons: Written to coincide with the marathon.

More from me at OZY.

In the New Year, expect a lot of Single-Digit Soccer and the start of the 2016 medal projections. Can’t wait.

The 2013 book extravaganza

This year, I’m doing a lot less freelance work and focusing on a few projects:

1. I’m following the Washington Spirit of the new National Women’s Soccer League through its debut season and will publish an electronic book as soon as possible after the season is finished in late August.

2. I’m writing about youth soccer, specifically the Under-10s and below, for a book called Single-Digit Soccer.

3. I’m still blogging at SportsMyriad and will work up 2014 Olympic medal projections.

Two opportunities to publish my work:

1. My book on The Ultimate Fighter is finished. My representative for publishing rights is Margaret O’Connor at Innisfree Literary.

2. If you’re interested in Single-Digit Soccer, please contact me. I’ll also be open to deals on the Washington Spirit book, but I plan to push that out quickly and won’t be going through the usual publishing process.

If you need me for soccer, MMA or Olympic writing, feel free to contact me. I’m limiting my time but will listen to good offers. The work doesn’t have to pay a ton — if you think the topic is up my alley, go ahead and ask!

As always, enjoy following SportsMyriad and my lively duresport Twitter feed, where I always seem to find a good soccer argument.