The U.S. Soccer Annual General Meeting provided expected drama at some points, unexpected non-drama at others, and unexpected drama at others.

I’ll get to the bit about the guy who called out the women’s national team for its sportsmanship.

Going bit by bit …

The Powers That Be may once again find themselves at war with the state reps.

U.S. Soccer’s National Council includes representatives from every state youth association (Youth Council), every state adult soccer association (Adult Council) and every pro league (Pro Council, dominated by MLS). Each group gets an equal share of the votes, a little more than 25% per Council. The Athletes Council, most consisting of those who played for a national team less than 10 years ago, is required by law to have 20% of the vote. The rest go to an assortment of associate organizations, individual board members, past presidents and Life Members (that’ll come up later).

Any organization can make a proposal to change the bylaws or policy manual. This year, the Metropolitan DC-Virginia Soccer Association (adult) had a policy proposal to slash registration fees across the board, except for pro leagues. Organizations would pay $5,000 rather than $10,000. Youth players’ fees would be 10 cents, down from $1. Adult fees would get a similar cut, from $2 to 20 cents. The goal was to erase barriers to participation for low-income families.

To get through all this, let’s go to the video …

At 38:45, when they’re about to vote to approve the budget, the MDCVSA rep stands up to get clarification on the procedure of the day. Can we approve the budget now, he asks, but then discuss the policy proposal later and, if it passes, get the staff to go back and adjust the budget? The answer is yes.

Fast forward to 53:15 for the big showdown between the MDCVSA rep and parliamentarian Michael Malamut, who says the board has decided not to recommend the dues changes, and that means the policy proposal is out of order.

Block out 10-15 minutes to watch what happens next. The MDCVSA rep was prepared, leading to a discussion of Roberts Rules of Order and such. Malamut, who’s been doing this forever, also knew his stuff.

No one raised his voice, though there was some interrupting. It was certainly tense. Under pressure, Malamut said the chair of the meeting has a decision to make, effectively punting to president Carlos Cordeiro to weigh in.

Eventually, Bylaw 212 is cited, supposedly to demonstrate that membership fees are recommended by the board and approved by the National Council by a majority vote. I don’t see that in the 2019-20 bylaws, but let’s assume for a minute that it’s correct. Does that means the only opportunity the National Council (again, all the members) had to question the membership fees was when the budget was discussed thirty minutes earlier? Or not at all?

Cordeiro agreed with Malamut but offered the olive branch of a task force. It may not be much, but it’s something.

I’ll get to the bit about the guy who called out the women’s national team for its sportsmanship.

The next policy proposal, essentially to require more detail in board and committee minutes, also caused some consternation between the representative (from Cal North), Malamut and Cordeiro. The Cal North man offered some concessions to exempt certain committees, at least for this year. That wore down the resistance, and the proposal was approved by a wide margin, to my surprise.

Earlier, West Virginia withdrew its proposal to require equal representation between men’s and women’s leagues in the same tier (in other words, MLS and NWSL). The Rules Committee had said it should be a bylaw rather than a policy. West Virginia’s Dave Laraba, who could probably be elected USSF president and Santa Claus in the same year if it was up to the states, said he respectfully disagree with the Rules Committee but would work toward re-submitting next year.

“We do urge the Pro Council to deal with this issue on their own, which they have the power to do,” Laraba said.

The weirdest state-related thing: Illinois’ adult association, which drew attention two years ago as one of Eric Wynalda’s most outspoken supporters in the presidential race, didn’t even speak on behalf of its proposals on Pro League Standards (punted because the Federation is being sued on that matter — feel free to contact the NASL about dropping that suit so the Fed can actually discuss this) and procurement (voted down rather heavily, in part because it was incomprehensible).

I’ll get to the bit about the guy who called out the women’s national team for its sportsmanship.

Cindy Cone was re-elected as vice president. This was contested but not contentious.

One year after being unanimously elected to fill the VP slot left empty when previous VP Carlos Cordeiro was elected president, the Hall of Famer won convincingly but far from unanimously over John Motta.

Worth remembering: The Athletes Council surely gave its 20% to Cone. The Pro Council probably gave all or most of its vote to her as well. Motta is the U.S. Adult Soccer Association president, so the Adult Council’s 25% and change surely went mostly to him. So the Youth Council and miscellaneous votes probably leaned toward Cone.

In any case, the candidates were gracious. Motta’s still on the board, and he’s anything but vindictive.

I’ll get to the bit about the guy who called out the women’s national team for its sportsmanship.

The good news: Everyone loves the Federation’s Innovate to Grow grant program, which is funding several initiatives on women’s coaching education.

Paired with the newly announced Jill Ellis Scholarship Fund, which has more than $200,000 in donations so far, the Federation is clearly taking steps to address a long-standing problem.

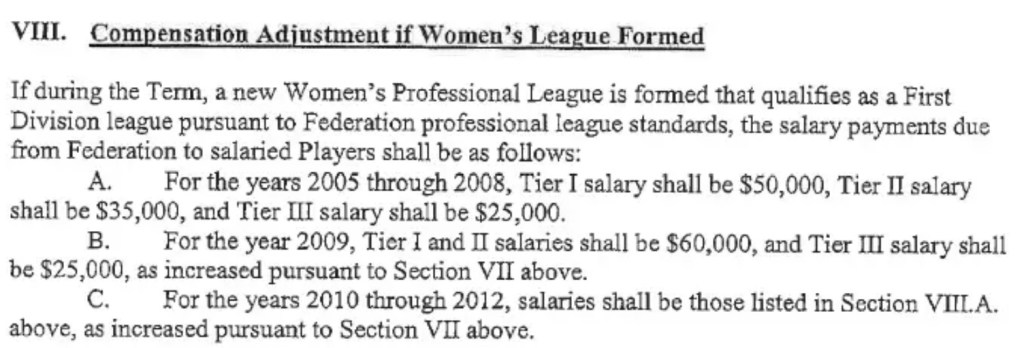

And let’s be clear — if national team pay is tripled, programs like this will be in serious jeopardy. Do the math. If you end up with a choice between training 200 female coaches and helping national teamers upgrade their cars, which would you choose?

I’ll get to the bit about the guy who called out the women’s national team for its sportsmanship.

Some members don’t understand legal obligations. An Athletes Council proposal to put athletes on grievance panels was a no-brainer. Literally. The Federation can’t afford to think about it because legal trends point rather heavily toward giving sports governing bodies no choice in the matter.

And yet some people voted against it. In an era in which legal fees are taking a big bite out of the Federation’s image and bottom line, they were happy to invite more lawsuits. Just to spite the Athletes Council?

OK, fine. Here you go …

Someone took issue with the women’s national team’s celebrations in the World Cup.

The man in question is Stephen Flamhaft, who’s been around forever. He is NOT on the board or in any other position of power. He’s one guy. Some people applauded, and they must have been near the microphones, because people at the AGM said they were sparse and that there were boos as well. Then several speakers took issue with him.

This isn’t the first time Flamhaft has made waves from the National Council floor. In 2005, he made a speech that reads like a plea to let board officers work until they drop. (See my 1998-2009 piece again.) In 2016, he rose to denounce Chuck Blazer, which was more controversial than you might think. See my 2010-2017 piece, then this thread.

This time, his comments were ill-timed and ill-stated. There’s no need to dredge this up again.

But, just like last summer, the Twitter reaction was so far overboard that it can’t be reached with a life preserver.

A little perspective — and yes, I know I’m speaking from male cis hetero financially comfortable privilege here. I’m also speaking from experience. While I sometimes agree with the “OK Boomer” sentiment, a lot of you whipper-snappers are just ageist. (Besides, I’m Gen X. We were handed Nirvana (good band) and Reality Bites (horrible movie) as our cultural touchstones, and we’ve been ignored ever since while the Millennials and Boomers …

So anyway …

Earlier this week, I watched the ESPN 30 for 30 documentary I Hate Christian Laettner, about the legendary Duke player (legendary for college play; in the NBA, he was a one-time All-Star, and that’s about it) and the fact that hating him was, and to some extent still is, a national pastime.

Did he commit a violent crime? No. He’s … arrogant. Overexuberant. A fierce competitor.

And people hate him.

That’s not surprising. A lot of people hate arrogant athletes.

And male athletes get pissed off when opponents celebrate too much. In baseball, if you flip your bat or do a slow home run trot, you may get a fastball to the ribs. Or the benches may clear. All part of baseball’s unwritten rules, much like the code (which is clear as mud, to be honest) in hockey.

The typical men’s sports controversy lasts for 24 hours. It feeds a cycle of talk radio and TV, then dies.

The WNT’s celebrations against Thailand stayed in the news because the women kept making reference to it and because of the rampant and grossly unfair accusations that anyone who questions the WNT’s behavior is sexist and misogynist.

Period.

Of course, there are some knuckle-dragging idiots out there. Always are. If you ever click a trending topic on Twitter and sort by “latest” instead of “top,” you’ll think civilization is speeding toward collapse. (It might be, which is another reason the U.S. men will never win the World Cup. I don’t cover that one in the book.)

But the defensiveness is over the top. It was last summer, and it was yesterday, where a lot of the ridiculous arguments popped up again.

They’re jealous because the men don’t win anything.

The Gender War is far from productive, and it’s unfair to current MNT players who face a much more difficult gauntlet of competition along with entrenched historical and cultural factors (see my book) that the women have never had to face.

I’ll argue that this can be fixed, though, by borrowing from Australia’s “equal pay” (it’s not) solution. The prize money for World Cups and other tournaments would still need to be addressed, but other money is put in one pool and evenly split between the men and women. That way, the men and women don’t just have a patriotic and cultural incentive to cheer for each other. They have have a financial incentive as well.

The women could beat the men

No.

The result making the rounds last year was a scrimmage between FC Dallas’ U15 team and the WNT, which ended 5-2 to the little guys. A fact check argued that the result was “decontextualized” because it was a “structured practice.” Perhaps, but the reason the WNT was playing a U15 team — and not even the full national team, just one very good club U15 team — was because it would be a comparable level of athleticism. It’s actually a common practice. They scrimmage youth teams because they would gain nothing by trying to match up with full-grown men.

And there’s nothing wrong with that.

We don’t build up Mikaela Shiffrin at the expense of Bode Miller. We can celebrate Allyson Felix even though her best time (21.69) in her best event (200 meters) was beaten by more than 70 male runners in the 2016 Olympics. We don’t fret about how Elena Delle Donne would fare in the post against … I don’t know. I don’t follow the NBA that closely.

Athletes are human.

They’re not people to be put on pedestals. Some of them are decent people. Some are even great. Even they make the occasional questionable decision.

A bigger issue in women’s soccer is coaching. It’s appropriate that Ellis is the namesake of a scholarship fund because she is the only woman among the 49 U.S. coaches to earn the new-ish Pro license. The United Soccer Coaches convention is so overwhelmingly male it makes a Star Trek convention look like Lilith Fair.

(For the record, I loved Lilith Fair.)

No one benefits from BS. No one benefits from misplaced priorities.

We need more women to stay in the game and coach. We need better youth development for men and women.

That’s why I point out the short-sighted and divisive arguments men’s and women’s senior national team advocates make in the pay debates. That’s why I think we need to find a way to get men’s and women’s fans and advocates on the same page.

One Nation One Team, indeed.

So we’re taunting the men’s national team over the women’s national team’s success, even while the men speak up for better pay for women. We’re touting proposals to pay the national teams at the expense of programs that grow the game, the opposite of what other (better) federations do.

So is Flamhaft a bit of a dinosaur? Sure.

But at some point, we should quit bashing the low-hanging fruit and climb a little higher on the tree.

(OK, Gen Xer.)